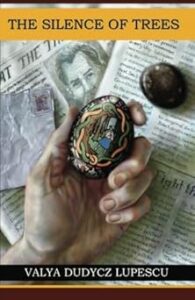

The novel The Silence of Trees grew out of questions about memory, migration, and the untold stories carried across borders and generations. In this 2011 conversation, Ukrainian American author Valya Dudycz Lupescu shared with me how those elements shaped her debut novel and the choices behind it. Hearing it again in 2026, I’m struck by how little the intervening years have dimmed its relevance.

Transcript: 2011 Interview with Valya Dudycz Lupescu

Pawlina: Valya Dudycz Lupescu is a Ukrainian‑American author from Chicago who recently released a novel called The Silence of Trees. It is her first novel. It is set in contemporary America as well as post–World War II Ukraine. And some listeners might recall the early days of this novel, which was very popular on Amazon.

Valya and I spoke a few weeks ago on Skype. Thanks so much for joining us, Valya.

Valya: Thank you so much for having me.

Pawlina: So this is your first novel, and you live in Chicago.

Valya: I do. I did live in Frankfurt, Germany for a few years, but Chicago is home.

Pawlina: Okay. Were you born in the States?

Valya: I was, in Chicago.

Pawlina: That’s where your roots are. Great. So now you’ve written a book called The Silence of Trees, and it’s a story that’s known by most people, particularly in America. So tell us a little bit about the storyline.

Valya: Sure. The story begins with our heroine, Nadia, at the age of 17. She is living in a small village in Western Ukraine at the time when Ukraine is occupied by the Germans, but the Russians are coming back. So it’s one of those changing fronts — the final change. This would have been in 1944.

And while their village has been fairly peaceful for a little while, that’s all about to change and explode. Nadia hears that there is a gypsy fortune‑teller camped outside her village, and all of the young girls sneak out and have their fortunes told. She wants to do the same, and her mother is absolutely against it.

And of course, Nadia, at that age, with dreams of what the future may hold, decides that she will sneak out in the middle of the night and have her fortune told. And so she does — but what she encounters is not what she expects. And when she returns home, she finds her family’s house and barn on fire, and they’re gone. She never sees them again.

She decides to flee west with the man that she loves. And soon he’s also taken, and she’s alone. She travels to the work camps, then to the displaced persons camps in Germany, and eventually meets the man she marries and moves to America to begin her life there.

So much of the story flashes back and forth between the past and the present. The story began while I was in graduate school at the Art Institute, and I was working on a nonfiction piece at the time about my grandparents’ immigration. It was a time for me to really ask them questions I had wondered about for a long time. And I was surprised that they were very secretive and reluctant to talk about that time.

As I started talking with other people of that generation, I heard the same thing again and again — this isn’t something they talk about. It was a mixture of fear for their families still left in Ukraine, and also feelings of guilt for those they left behind and the way their life was.

So I started collecting interviews and doing more research. This was back in the days before the Internet had so much available. And I realized that the story I wanted to tell wasn’t a nonfiction piece after all — I wanted to get into the heart of these characters, these people. So I created a fictional story, but very much based on the stories I was hearing.

So many of them had never spoken about this time. This was the first time they did — to me. And when I started writing the novel, I wanted to capture the complexity of that character and tell those stories that had never been told, precisely because they were so valuable and in danger of being lost forever.

Pawlina: It’s amazing how you did that, because people of that era don’t want to talk about it. There’s shame, and there’s probably fear, as you said — that there could be repercussions, or maybe it’s an ingrained fear. How did you get them to talk?

Valya: I guess I have a trusting face. Ever since I was little, I was the kid in the corner listening. And when I would get on the bus, I was the one people would sit next to and tell their life story. So perhaps it’s something they pick up on.

I would never disclose information people didn’t feel comfortable sharing. Many times they would say, “I’m going to tell you this, but please don’t record this,” or “Please don’t record this specific name or village,” because there was still a lot of fear. This was a time in history when people changed their names — intentionally and unintentionally — coming to America or another country. They tried to leave behind their past.

So there was a trust I established with the people I spoke with, my grandparents included. And the events that happen to Nadia are fictional — this isn’t any one thing or any collection of things that happened to my grandparents or people I know. But at the same time, it’s very true, because it is like what happened to many of the people I spoke with or read about later — not just Ukrainians, but many Eastern Europeans who went through World War II.

Pawlina: Was there a turning point that made you decide you wanted to write fiction after all?

Valya: I’d been sitting in a class. We had a guest speaker, Stuart Dybek, a Chicago writer of Polish descent. He has written several wonderful collections of short stories, one of which is The Coast of Chicago. In his stories, he really captures the flavor of the ethnic neighborhood and characters you can relate to — they felt very real.

Prior to that, I don’t know — I felt as if I didn’t have permission to write about these everyday people I had grown up with. And then hearing him read and talk about it, I realized that may be precisely the reason I should write these stories.

It was Halloween, and I remember going home and writing the first three chapters of the book that night. That was the turning point. The characters came to life and I couldn’t silence them. So I kept going.

Pawlina: Wow. Now, your book is called The Silence of Trees. Is there a particular reason you chose that title? Does it have any significance?

Valya: Of course — but I can’t spoil it and tell you exactly why. It has a lot of meaning. It’s multifaceted.

There are many different kinds of trees, both literal and figurative. There are the trees Nadia sits beside in the camps. There are the trees in America. There’s the idea that the ancestors go into the trees when they pass away. And we bring in their leaves and greenery for Zolota Nyzviata. So there are a lot of different trees in the book, and the title echoes all of those meanings.

Pawlina: You incorporate a lot of tradition, a lot of background. Nadia holds on to her Ukrainian heritage, as so many postwar immigrants to Canada and the United States did. And you wove that in very nicely.

Valya: Thank you. It was very much a part of what I wanted to preserve. I think it informed her character a great deal and reflected that time period. But at the same time, in writing this book, I wanted to honor those men and women of that time, and also preserve some of these traditions.

It’s been interesting in recent days when I’ve met some of the newer immigrants to America — those who came over in the ’90s and more recently. For many of them, the stories of the displaced persons camps and some of the traditions held so strongly by my baba and dido have been lost or never learned. So for many of them, as they read these traditions, they’re surprised — they’re learning. And there is a movement among younger people in Ukraine right now to recapture some of those lost traditions.

Pawlina: That’s great. Isn’t it fabulous to know your book is part of that?

Valya: Absolutely. The novel also falls into a genre called magic realism. It was a deliberate choice — a literary device to create a world that is real. It’s not fantasy. It’s a realistic world, especially with the grim reality of World War II. But there are magical elements — superstitions, dreams that come true, little things you see out of the corner of your eye. That creates this idea of magic realism — two worlds, the magical and the realistic, coexisting.

Nadia’s reality is very much that of a person caught in the threshold between the old world she left behind in Ukraine and the new world she’s embracing in America. Magic realism reflects that part of her character. And it’s something I felt even as a second‑generation Ukrainian‑American woman. I think it’s the same in Canada and many parts of the United States — children of my generation grew up speaking Ukrainian before English, going to Ukrainian school, dancing, church. There was a big part of our identity that was Ukrainian, and then the Western part — our friends from school. So it was this idea of standing in the threshold between two worlds, which I found fascinating about Nadia.

Pawlina: You’ve been working on this book for a long time. Just before I turned on the record button, you were saying that back in 2008 you started to promote your book even before the publisher had it. Tell us a little about that.

Valya: Yes. I started the book while I was still in graduate school, in 1995. It took me on and off about ten years to write. I did a lot of research in the beginning. Then I had three children, which put writing and promoting on hold. We moved to Germany, came back to America, and moved back to Germany again.

The last time we were living in Germany, in 2008, my youngest was finally sleeping through the night. I heard about the Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award, where unpublished manuscripts were submitted and small sections were made available for readers to review. At that time, we weren’t sure how winners would be chosen, but the idea was to get as many votes as possible.

I was thrilled and humbled by the support — especially from Ukrainian people in Ukraine and the diaspora — who galvanized, spread the word, read the section, and voted positively. It got media attention in the States and Europe. Radio Free Europe called me for an interview. It was very exciting.

After that, I got the attention of an agent through the contest and began down this road. For so many writers starting out, you have to do much of the promotion yourself, whether it’s a small press, independent press, or even some larger publishing houses.

I’ve been using social networking sites — as you say, we met on Twitter — spreading the word that way. I’ve been able to get some well‑known reviewers to review the book and spread the word. Sales on Amazon have been fantastic. We live in a different world.

In August, we sold over five thousand Kindle books of The Silence of Trees. It was ranked 66 of all Kindle books on Amazon. It was remarkable to think that so many people were reading Nadia’s story and the experiences of this woman.

Pawlina: Congratulations — that’s great. I had an eye injury, and when you sent me the book I was having trouble reading the print copy, so I found a copy on Kobo. That’s great — great to have this story being circulated like that.

And thanks for coming on and telling us about it. Hopefully we can get more readership for it yet. I personally think it’s a fabulous story and one that no one should miss out on. So thank you for writing it.

Valya: Thank you for having me and for telling people about it. And hopefully there will be a sequel, a prequel, or more like it.

Pawlina: Someday?

Valya: Yes — there’s another book in the works for sure.

Pawlina: Awesome. Good luck with your next novel.

Valya: Thank you.

Pawlina: And I was speaking with Valya Dudycz Lupescu, author of The Silence of Trees. Valya has very kindly offered two copies of her novel to Nash Holos listeners, and she’s offered to autograph them for you, personalized if you like.

Email producer@nashholos.com and give me your name, phone number, and address so Valya knows where to send the book. Also tell me which edition of Nash Holos you heard the contest details on — whether it was the broadcast on Sunday, October 9th in Vancouver, the podcast, the PCJ International Edition podcast, or the live broadcast on the PCJ Radio Network on any of the partner stations.

That’s what you need to do to enter the email draw. You do need to get that to me by the end of October.

The Silence of Trees

Valya Dudycz Lupescu

Publisher: Wolfsword Press

Publication Year: 2010

ISBN: 9780982744508

Page Count: 286

Format: Paperback and e‑book